Don't let your code dry

I’ve been mutation testing for 11 years now, ever since I first stumbled across the technique. There were people doing it in Java before me, but not many. So not only do I maintain the main tool, but I also have some of the most extensive experience of how to apply it in practice.

So here’s the thing, mutation testing is getting more popular now, but most of you are doing it wrong.

The first mistake everyone makes

Most teams don’t run mutation testing often enough, and because of that it doesn’t add much value.

Running pitest in an overnight CI job, or at some other infrequent interval, seems to make sense. It’s a computationally expensive process. If it takes an hour to analyse your code base, you can’t run it on every push can you? And because it’s on a CI server you know it will get run. And that’s good right?

The problem with this approach is that you gain nothing by running mutation analysis. Zero. Zilch. Nada. ничто.

Running mutation analysis is where all the cost is.

You don’t get any benefit until you look at the results and do something with them.

Typically, if the analysis is run overnight, this doesn’t happen in a meaningful fashion. The results are largely forgotten and ignored.

The second mistake

Having setup mutation testing to run infrequently, many people try and make sure the results aren’t ignored by setting a target mutation score, so the build fails if the mutation score drops below a certain level. Pitest supports this because so many people asked for it, but it is not something I ever use myself.

It doesn’t really solve the problem, and can actually make things worse. The fundamental issue is you’re still only looking at the mutation testing results after all the work is “done”.

This late in the day surviving mutants are a nuisance. You thought the thing you were working on was all done and wrapped up, and now some tool is telling you there’s more work to do. Even worse, you’ve forgotten all the little details about what you did, so trying to understand each mutant takes lots of time.

You might add a test or two, or remove some obviously redundant code, but the motivation to make any major change is lacking. You’ll take the easy route to fix things, and that can make a codebase worse in ways that are difficult to measure. Adding a test that’s highly coupled to the code is often easy. Adding one that isn’t is much harder.

The way you react to feedback late in development is different from the way you react when the code is still wet. To use mutation testing effectively you need to do it before everything has dried.

How I mutation test

Here’s how I’ve been using mutation testing for the past decade or so.

- Make a change to the codebase I’m working on, adding code and tests

- Run pitest

- Look at the results

- Change some code or tests if I think the results showed me something interesting

- Repeat many times

- Push my change to the rest of the team

When I’m working on a small codebase I run pitest over everything. Often that takes just a few seconds.

As the codebase grows, that becomes less and less practical, so I start to limit the analysis to just the bit I’m working on. This is pretty easy to do.

For a maven build I usually set things up something like this

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

<profile>

<id>pitest</id>

<build>

<plugins>

<plugin>

<groupId>org.pitest</groupId>

<artifactId>pitest-maven</artifactId>

<version>1.6.4</version>

<executions>

<execution>

<id>pitest</id>

<phase>test</phase>

<goals>

<goal>mutationCoverage</goal>

</goals>

</execution>

</executions>

<configuration>

<failWhenNoMutations>false</failWhenNoMutations>

<timestampedReports>false</timestampedReports>

<mutators>STRONGER</mutators>

</configuration>

</plugins>

</build>

</profile>

Pitest is run only when a profile is active. By default, it will mutate everything in the project, but I can pass a glob on the commandline to limit the analysis.

1

mvn -Ppitest --DwithHistory=true -DtargetClasses="the.package.i.changed.*" test

The withHistory parameter tells pitest to use incremental analysis so, even if my glob is quite far ranging, the analysis will be fast after the first run.

This approach works. It works really well. It scales to codebases of any size. I get feedback on my code as I write it, at a point where I’m still receptive to changing what I’ve done.

Pitest nudges me to remove duplication and make my code simpler. It makes me a better programmer, even on the bad days when I’m not thinking straight. Pitest has my back and catches my mistakes for me.

There are some disadvantages to this approach though. I can forget to do it, so there’s no guarantee that pitest will be run. And when I do remember, it’s an invisible activity. No one knows its happened. This means that the practice is less likely to spread.

Pitest on the CI server

Since 2013 pitest has had a maven goal that integrates with version control. In theory, I could use this to mutate just my locally changed code without passing a glob around, but in practice I rarely do. There are some awkward edge cases caused by the fact that pitest works in terms of bytecode and java packages, while source control works in terms of source files on disk, and playing about with maven version control config can sometimes be less than fun.

The way I have used it, is to run pitest against pull requests. As only the changed code is analysed it’s fast, even on large code bases, but it’s never worked out particularly well for me.

The issue is that the output is not easily accessible. It’s not hard to access, but there are speed bumps in the way. It ends up as a report you have to download from the CI server, or a URL you need to find to click on to view.

It’s easy to ignore, and the feedback is slower than running it locally. So I mainly use this approach for reviewing other people’s code, rather than as part of my own feedback loop. And I still need to be aware of those edge cases I mentioned earlier.

So, pitest on the CI server has some uses, but I only ever use is as an addition to working locally, not as a replacement.

How does Google do it?

Google does mutation testing too. You can read all about it here.

Mutation testing at google is integrated into their code review process, presenting programmers with a random sample of surviving mutants in a diff. They report all sorts of improvements they’ve seen in the teams that are using it, and apparently 70% of bugs at google could have been prevented by a test written in response to one of their mutants.

So it’s working for them. It’s similar to my ‘pitest on pull requests’ approach, but the ergonomics are better. They’ve concentrated on removing noise and highlighting the mutants they think are most valuable. It’s less timely than my ‘mutate locally’ approach, but it’s still happening while the code is quite wet. That’s why it works.

It has some disadvantages though: it’s a build server only activity and is based on random sampling, so programmers can’t easily reproduce the mutants it highlights or confirm that they’ve fixed them. The feedback loop is always slower than mutating locally.

A better way to work

I’ve been doing some work recently to improve both my “mutate it locally” and “pitest on pull request” approaches.

It’s a two part solution. Firstly, a new pitest plugin integrates tightly with git. Unlike the existing version control integration it isn’t tied to maven, so it can be run from gradle or ant as well.

Once the plugin is added you can analyse just your local changes with

1

mvn -Ppitest -Dfeatures="+GIT" test

The analysis is more fine-grained than before. By default, it’s limited to just the modified lines. This means it takes less time, but more importantly it reduces the noise. The results you see are now only those that are actually in the change. This is true locally, but also when run against a pull request.

The problems with bytecode mapping back and forth have also been solved, so no more edge cases to worry about.

If I’m working with old code, and want to see what mutants look like in all the classes I touch I can replicate the old behaviour by running

1

mvn -Ppitest -Dfeatures="+GIT(scope[class])" test

But most of the time I want the faster, more relevant feedback.

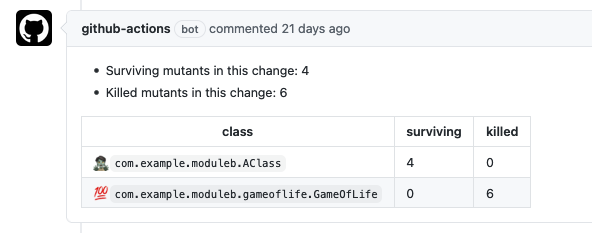

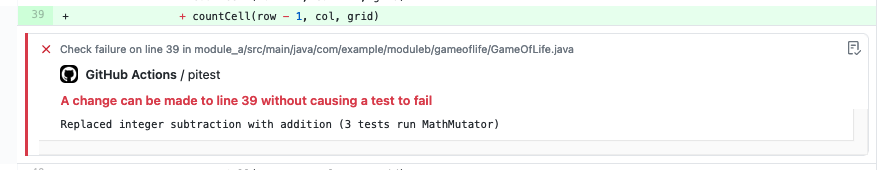

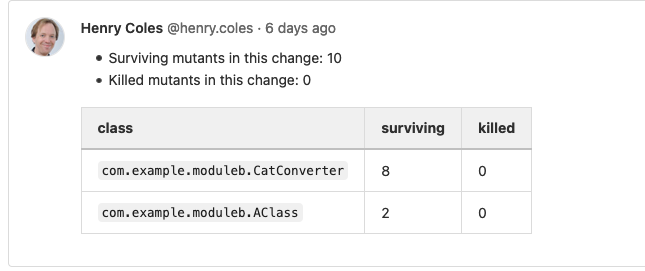

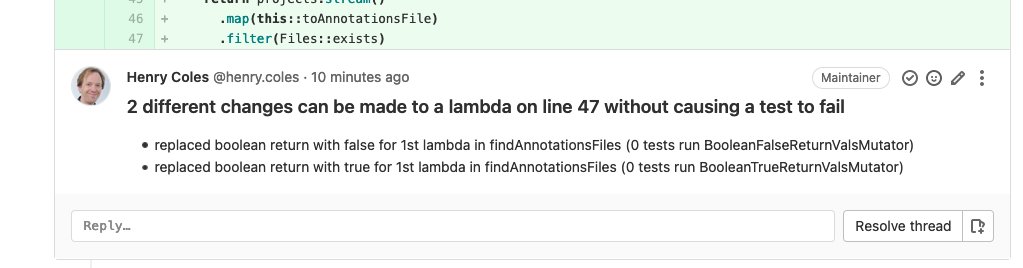

The second part of the solutions are plugins for maven and gradle that create comments and annotations directly in Github pull requests, and Gitlab merge requests.

Only the surviving mutants are displayed, and there are a few other tweaks to make the output clear and easy to understand.

The end result looks like this in github

My new workflow is

- Create a WIP pull request

- Code, push and look at the results in the PR

- Change some code or tests if I think the results showed me something interesting

- Repeat many times

- Merge the PR when ready

I augment this with local analysis when I want to improve the broader state of the code I’m working on before I make the change, or I want to get results faster.

Mutation testing is now a visible activity. Everyone gets the feedback. They’re free to ignore it if they don’t find it useful, but everyone on the team can see it happening, and in this way uptake and understanding spreads.

Want to try it?

The plugins are now available at arcmutate.

Unfortunately, due to the way that Github API access works, the plugins work well for closed source development, but are not yet a good fit for open source projects where pull requests come from potentially malicious sources in forked repos. We’re hoping to come up with a solution for this soon so everyone can benefit from pitest on their PRs.

Setting up pitest on pr for open source projects is slightly more involved as pull requests come from untrusted forks, but I’ve being trying out a solution that I’ll post about soon.